Good-quality pasture is nature’s gift to dairy cows. Not only is it well balanced between energy and protein, but also highly digestible to the ruminant. If managed correctly, pastures can be one of the most valuable feed sources for dairy cows.

A material risk for pasture-based dairy systems is that they are at the mercy of the weather and so the conditions are not always favourable to grow enough high-quality pastures. That is why pasture-based milk producers need to plan and account for seasonal changes. This article aims to provide some nutritional strategies to help ease the transition and optimise rumen function from summer through winter.

Every season has its challenges when it comes to feeding cows, especially on pasture-based dairy farms, where, on average, 60% of the cow’s diet is grown on the farm. Winter brings its own challenges in the form of cold and dry weather, which makes it difficult to grow pastures. This is on top of the decreased pasture platform after maize has been planted in the summer months.

Planning for winter

The aim when planning for winter should be to optimise the rumen function in the most cost-effective way. Rumen microbes help ferment fibre coming from the diet into volatile fatty acids, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These fatty acids can provide more than 60% of the cow’s energy requirements. Fibre or more specifically neutral detergent fibre (NDF), also helps with a proper rumen mat formation that provides the building blocks (acetate) for butterfat production, serves as a scratch factor, and stimulates cud chewing, which provides natural buffers via saliva. All of these factors work together to keep the rumen environment healthy.

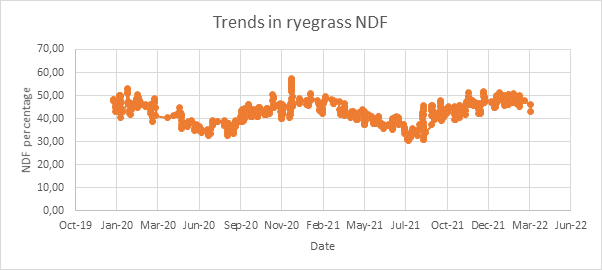

The graph below illustrates the NDF trend in ryegrass pastures in KwaZulu-Natal over the period of January 2020 until March 2022. There is a gradual drop in pasture NDF from March, with a low point in June, July, and August. It is, therefore, important to include additional roughage in your planning for this time of the year when fibre from the pasture is at its lowest. The best way to stimulate intake of the additional roughage, such as hay bales, is to mix it in when feeding maize silage. Since this is not always possible, the hay bales can also be processed by hand by loosening up the bale and providing it in a hay ring. The benefits of the additional roughage will be considerable, from buffering rumen pH to providing more protein and energy to the cow.

Pastures

Pastures are known to have a good amount of protein and energy available, especially in the spring and summer months. During this time, when pasture growth is best, degradable crude protein is normally not limiting. Unfortunately, as the plant grows older and prepares for reproduction, its nutritive value will start to change. The plant will become less palatable and less digestible, while also providing fewer nutrients (protein and energy) to the cow.

During flowering, pasture species undergo a change in morphology from vegetative to reproductive, where nutrients are channeled from the leaves and stem to the roots of the plant. Ryegrass pastures will start to flower depending on the length of the day as well as the day and night temperatures. Depending on the type of pasture, flowering will take place based on these changes. For example, Italian ryegrass varieties need cold night temperatures to induce flowering (vernalisation), while Westerwold varieties will start to flower based on the increase in day length and/or temperature, thus without the need for vernalisation.

The way we manage protein in the diet changes drastically from spring through summer and into autumn and winter when there is a short supply. It is important to note that cows do not have a real crude protein requirement, but rather for the metabolisable components of which crude protein is comprised. It is, therefore, more accurate to focus on the building blocks of protein (ammonia, peptides, and amino acids) as well as the different fractions of protein (rumen-degradable and undegradable protein) when formulating rations for winter.

Soluble protein

Rumen microbes need substrate in the form of rumen-fermentable energy and soluble protein to ferment fibre. If there is a short supply of soluble protein in the diet, these microbes will start to utilise rumen undegradable (bypass) protein and/or amino acids. This needs to be considered during winter when soluble protein from pasture is limited. Microbial protein is the best and cheapest source of metabolisable protein and, when managed correctly, can provide more than 50% of the cow’s metabolisable amino acid requirement.

In winter, with the reduction in pasture growth rates and pasture area, maize silage is often used to supplement dry matter intake and provide much-needed energy in the form of digestible fibre and starch. Rations should be well balanced based on the starch and NDF content of the maize silage to provide enough fermentable energy to the microbes without having a negative impact on rumen pH or cow health. High starch levels can be potentially dangerous and lead to laminitis, over-conditioned cows, and/or rumen acidosis, which will negatively impact cow health, production, and, ultimately, farm profit.

It is crucial to know the nutrient density of your on-farm feed when planning for your winter-feeding programme. Dairy rations are formulated with a specific goal in mind and are used to enhance the utilisation of farm feed. Pay attention to your herd’s milk urea nitrogen levels, faecal starch levels, undigested NDF levels, milk production, milk solids, and their body condition scores. Proper utilisation of

these tools will help you optimise the rumen to provide the cow with the most cost-effective sources of energy and protein even in the difficult winter months.